Visions of Egypt

It was impossible to believe. The pyramids rose before me, massive, monolithic, and ancient. Ancient beyond reckoning. So ancient that they appeared like mirages fluttering in the desert wind, as if transmogrified down the march of centuries, shifting in and out of time, an epochal paperweight. When humanity asks of its history, the pyramids stand sentinels at the gates of constancy.

From Cairo’s formidable ring road, the pyramids are often visible. Their immense bulk pushes against the sky, forming a bulwark against the passage of time. Imagining what they have seen and heard numbs your imagination. Pharaohs, dynasties, armies, religions, prophets, drought, war. The pyramids render you insensate to the passage of time. 4400 years of existence bear down. Things are either legend or fact. The pyramids are both. The pyramids give meaning to history.

Cairo itself is an immense rendition of post-colonial poverty pushed up against the 21st century. A city of towering antiquity struggling desperately to transcend the casual indignities of the present. A faded mishmash of every imaginable shade of brown. Spent by foreign powers, worn out by history, neatly sidestepped by the 21st century. From the neoclassical Talat Harb square to the Old City’s Al Moez, an air of genteel decay pervades the city. Here, on the banks of the Nile, in the shadow of the greatest artifact the world has ever seen, 22 million people eke out a living.

Sic transit gloria mundi. The centuries march. Civilizations rise and fall. The present is a fickle servant. Cairo, Magadh, Tikal, or Washington DC. Present turns into past turns into lore into myth. Will sand bury the Empire State building one day? Will dust hide Versailles? Will the Taj sink into the Yamuna? Will the Anthropocene irrevocably change the planet itself? Will the Persian Gulf become uninhabitable?

Such questions dissolve before Tutankhamen’s mask. If an artifact can radiate power, true power, then let it be Tutankhamen’s mask. If they pyramids arrest history, Tutankhamen’s mask arrests power. The mask transfixes your gaze. Unimaginable glories swirl in your mind as that fantastic mask dominates the space. The boy king, immortalized by an artifact fit for Gods.

Tutankhamen’s mask lies in Cairo’s Egyptian museum. Imagine a building stuffed with priceless riches thousands upon thousands of years old. The artifacts lie, piled, overwhelming the corridors, open to touch. Walking the museum’s dusty corridors finish what the pyramids began. You lose all conception of time. The centuries lose meaning. The world is ancient beyond reckoning. Mortal minds, born of short lives, fail to deal with the monumental, preferring instead the comfort of the trivial.

Outside Cairo, on a dusty desert plain near the Nile, lie the first pyramids. Here, you feel the desert. At Saqqarah and Dahschur, the desert stretches endless, horizon to horizon. The Nile, behind you, the life-giver. The White Nile from the Ruwenzori Mountains in Uganda (Ptolemy’s famous Mountains of the Moon), and the Blue Nile from Laka Tana in Ethiopia; the water gave birth in the desert to a flowering of civilization never seen before in the known universe. And here, at Saqqarah and Dahshur, that flowering began. With the Black pyramid, the Bent pyramid, and the pyramid of Djoser. And so, arguably, began history itself. One star in the trinity of the ancient world: Egypt, Mesopotamia, and India.

No doubt these peoples traded and talked. What did they conceive? What were the markets of Harappa, Uruk, and Giza like? What was the New York City of the ancient world? Did Egyptian, Semitic, and Indic languages ever co-exist 6000 years ago?

In our homes, these questions appear silly. But in Egypt, every grain of sand has a story to tell. Perhaps a story of Queen Hatshepsut scheming for the throne. Of Ramses II fighting the mammoth Battle of Kadesh. Of Tutankhamen’s glories. Of the Khufu and Khefre raising the pyramids. The air is choked with history and every civilization adds another layer: the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom, the New Kingdom, the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Byzantines, the Sasanians, the Umayyads, the Abbasids, the Fatimids, and the Mamluks. Your mind grasps, unable to comprehend such vastness. You can only stare.

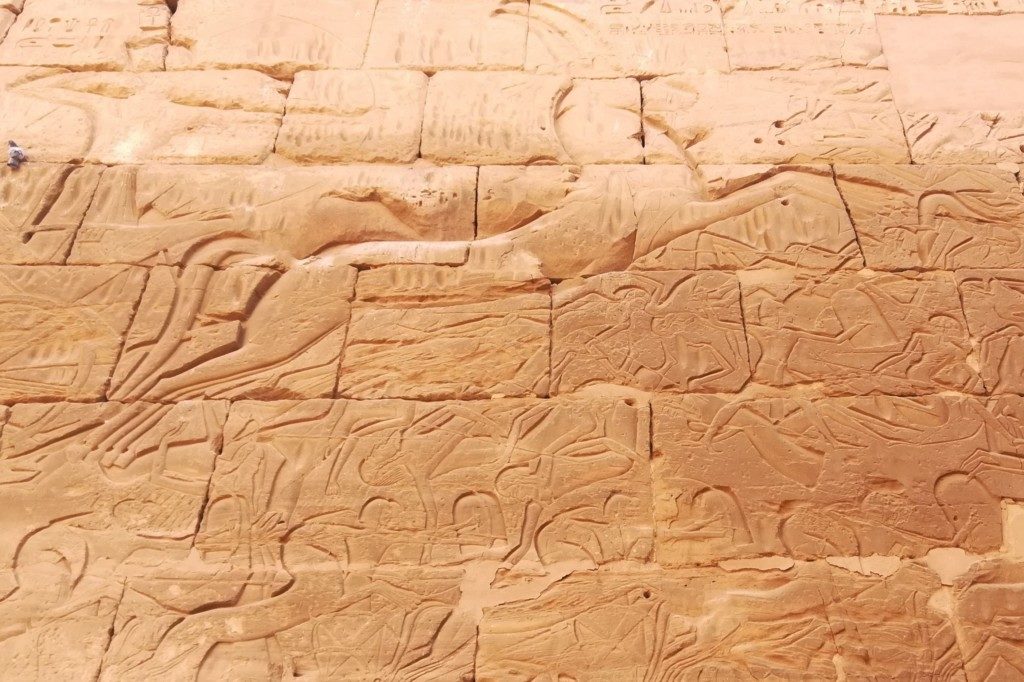

Stare at the reliefs in the tomb of Ramses IV. At the Hypostyle Hall in the temple of Karnak. At Hatshepsut’s obelisk just beyond. At the gates of the temple of Horus at Edfu. Or at the murals of Rameses II at Medinet Habu. Rameses’ chariot arcs, horses yoked, rearing impossibly high over a writhing mass of soldiers locked in war, their bodies interlocked and undecipherable, delivering unto Egypt its god-given glory at the Battle of Kadesh.

For Kadesh was the largest chariot battle in history. There was nothing like it, before or since. Between the Egyptians and Hitties. Oddly enough, Kadesh resulted in the first known peace treaty 15 years later. Let us read this seminal sentence in human history, for this sentence relates not just to Egyptians or to Hittites, but to something deeper, to the very human quality of forgiveness, even amongst blood enemies:

Behold, Hattusilis, the Great Prince of Hatti, has set himself in a regulation with User-maat-Re Setep-en-Re, the great ruler of Egypt, beginning from this day, to cause that good peace and brotherhood occur between us forever, while he is in brotherhood with me and he is at peace with me, and I am in brotherhood with him and I am at peace with him forever. Now since Muwatallis, the Great Prince of Hatti, my brother, went in pursuit of his fate,9 and Hattusilis sat as Great Prince of Hatti upon the throne of his father, behold, I have come to be with Ramses Meri-Amon, the great ruler of Egypt, for we are together in our peace and our brotherhood. It is better than the peace or the brotherhood which was formerly in the land. Behold, I, as the Great Prince of Hatti, am with Ramses Meri-Amon, in good peace and in good brotherhood. The children of the children of the Great Prince of Hatti are in brotherhood and peace with the children of the children of Ramses Meri-Amon, the great ruler of Egypt, for they are in our situation of brotherhood and our situation of peace. The land of Egypt, with the land of Hatti, shall be at peace and in brotherhood like unto us forever. Hostilities shall not occur between them forever.

Source

If only such hostilities never re-occurred forever. Still, we must begin somewhere, and if not Kadesh, when?

History lies thickest at Karnak though. Built of thousands of years by successive pharaohs, there is little point bringing language to bear on Karnak. Simply put, Karnak is hard to believe even when seen. Attempting to describe the grandeur of the Hypostyle Hall in the late afternoon Sun itself would fill a tome. To be dwarfed by the Hall’s columns is a rare pleasure.

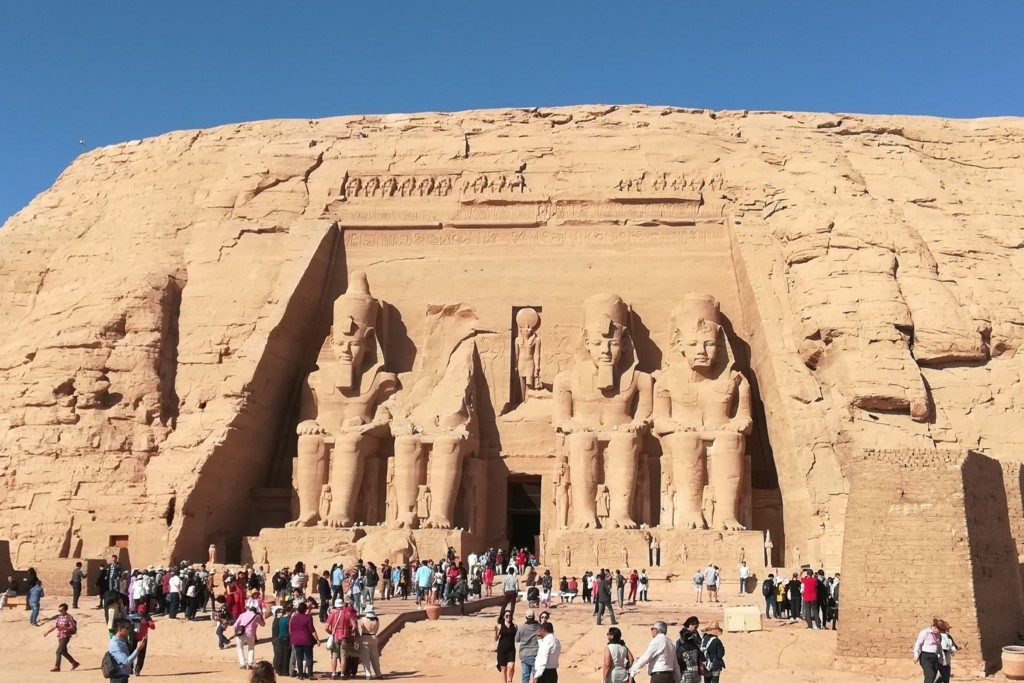

From Karnak and Luxor, the pilgim inevitably ends at Abu Simbel. Where Cairo and Luxor connect to the Mediterranean, Abu Simbel feels firmly in Nubia. Here lies Egypt’s southern border. On the shores of Lake Aswan, the temple of Abu Simbel is the place to stop, ponder, and meditate. Outside the temple walls, the four massive statues of Rameses II stare into the distance. The statues smile slightly, as if Ramses II, the greatest of all pharoahs, saw something we do not. Dying at 90, after 66 years of rule, history no doubt spoke differently to Ramses. Whatever it was, it was lost on me. I hoped this essay would lend comprehension but instead I learnt how little I know.

The tapestry of history is rich and layered. Every voyage uncovers a little. Little by little the picture builds. The threads meet, weft, form. You see the flow of history in the people, the laws, the cultures, languages, traditions, festivals, rituals, pilgrimages, customs, gestures, precepts, values, structures. This is why we travel. To understand the tapestry that created you and me. In the peace treaty of Kadesh or the obelisks of Karnak or the pyramids of Giza. For why exist in the 21st century if not to bend our minds to this very task?